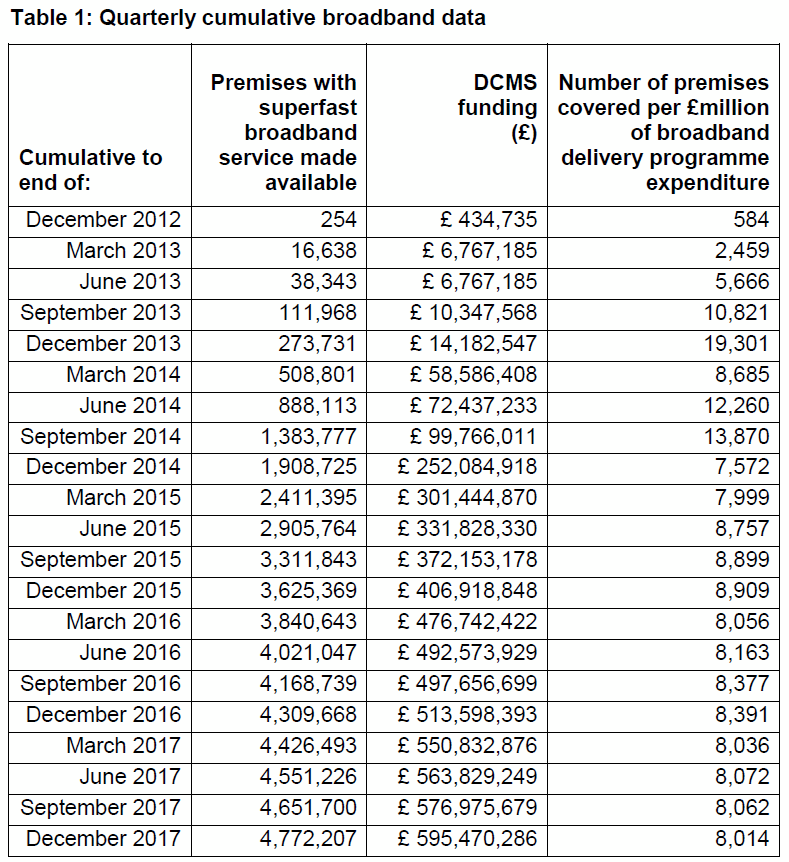

Q4 2017 BDUK Build Superfast Broadband to 4.77 Million Premises

The Government’s £1.6bn+ publicly funded Broadband Delivery UK project has published its latest progress update to the end of 2017, which reveals that it has so far helped 4,772,207 extra premises across the United Kingdom to be reached by a fixed “superfast broadband” (24Mbps+) network.

At present more than 95% of premises in the UK are estimated to be within reach of a fixed line superfast broadband network. The next step will be to extend this to 98% by around 2020, while the final 2% will be largely tackled via a mix of alternative network providers (altnets) and the forthcoming 10Mbps Universal Service Obligation (USO).

Most of the BDUK roll-outs have been supported by contracts that harness Openreach’s (BT) ‘up to’ 80Mbps Fibre-to-the-Cabinet (FTTC) and a small bit of their ultrafast Fibre-to-the-Premise (FTTP) technology. More recently we’ve also seen altnets like Gigaclear, Call Flow, UKB Networks and Airband win a number of contracts, particularly around the more remote rural premises where Openreach tends to struggle.

Advertisement

We should point out that the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) are planning to cease publication of this statistical release, with the final update due in May 2018 and that will cover data up to March 2018. This is somewhat disappointing because we are still expecting BDUK linked deployments to continue into 2020 and tracking progress will become harder.

Q4 2017 Progress Report

The “premises passed” figure used below only reflects those properties (homes and businesses) able to access “superfast” speeds of 24Mbps+ as a result of BDUK linked investment (i.e. it excludes those that have benefited but which only receive sub-24Mbps speeds). Similarly the data excludes “overspill effects” of BDUK-supported projects on premises which already have superfast broadband.

NOTE: The table only shows state aid from the Government’s project (BDUK) and does NOT include match-funding from local councils, the EU and other public or even private sources.

Advertisement

The headline figures used above are said to be cash based (i.e. when grants are made or budgets transferred). On an accruals basis, which matches costs incurred to the timing of delivery, cumulative BDUK expenditure to the end of December 2017 has been estimated as £620,875,323 and that equates to 7,686 premises covered per £million of BDUK expenditure (expenditure is higher for this because the work has been delivered in advance of payment).

The roll-out pace has slowed somewhat but that was to be expected because the programme has now reached some of the most challenging rural and tedious sub-urban locations (e.g. Exchange Only Lines), which take longer to reach, cost more and deliver fewer premises passed in the same space of time.

There’s also a question mark over the impact of clawback (gainshare) on the figures, which sees suppliers like BT return some of the public investment when take-up goes beyond the 20% mark in related areas. So far up to £527m could potentially be returned (here), which can then be reinvested into further broadband improvements. On top of that around £210m from efficiency savings will also be available (here).

Most or all of the above funding / reinvestment will be used to help bridge the gap between 95% and 98% coverage by 2020.

Advertisement

NOTE 1: Future deployment phases (i.e. those aiming to deliver coverage above 95%) will be adopting the slightly improved 30Mbps+ definition for “superfast broadband“. The EU and Ofcom have been using this definition for many years, although official BDUK contracts were slow to do the same.

NOTE 2: The above expenditure figures exclude support for Connection Vouchers, the Mobile Infrastructure Project, the Rural Communities Broadband Fund, the Market Test Pilots, DCMS administrative expenditure and the new “Full Fibre” programmes.

NOTE 3: As we reported in October 2017 (here), BDUK supported projects have overbuilt some of Virgin Media’s network to the tune of around 1 million premises, although such premises are not eligible for public funding and so haven’t been included into the above total.

NOTE 4: The commercial market (i.e. purely private investment) has already enabled operators, such as BT and Virgin Media, to extend the reach of superfast broadband to around 76% of UK premises. However the major operators’ tend to view many of those in the final 25% as being “not commercially viable,” hence the reason for BDUK being setup to boost the roll-out via public investment.

Mark is a professional technology writer, IT consultant and computer engineer from Dorset (England), he also founded ISPreview in 1999 and enjoys analysing the latest telecoms and broadband developments. Find me on X (Twitter), Mastodon, Facebook, BlueSky, Threads.net and Linkedin.

« iD Mobile Becomes First UK MVNO to Launch Wi-Fi Calling

Comments are closed