Most EU Countries and UK Set to Miss Targets for Fibre Access

New research from Analysys Mason, which was commissioned by Chinese technology firm Huawei (vested interest), has today warned that the United Kingdom and most EU countries will miss the European Commission’s (EC) future broadband targets unless they tackle the remaining challenges and barriers being faced by operators.

A few years ago the EC proposed several new, albeit non-binding, Gigabit Society targets for “all European households” to get a minimum download speed of 100Mbps+ by 2025 (this must be upgradable to 1Gbps), with businesses and the public sector being told to expect 1Gbps+ (here). The UK Government has also recently committed £5bn to help cover every home with “gigabit-capable” broadband by the end of 2025 (here).

The new report – ‘Full-fibre access as strategic infrastructure: strengthening public policy for Europe‘ – similarly notes that national governments across Europe are increasing investment in fibre broadband ISP networks, but it warns that this alone is “unlikely to be enough” to achieve the targets. Similarly European regulation has tended to favour fostering retail competition and low prices over long-term investment, which doesn’t always help.

Advertisement

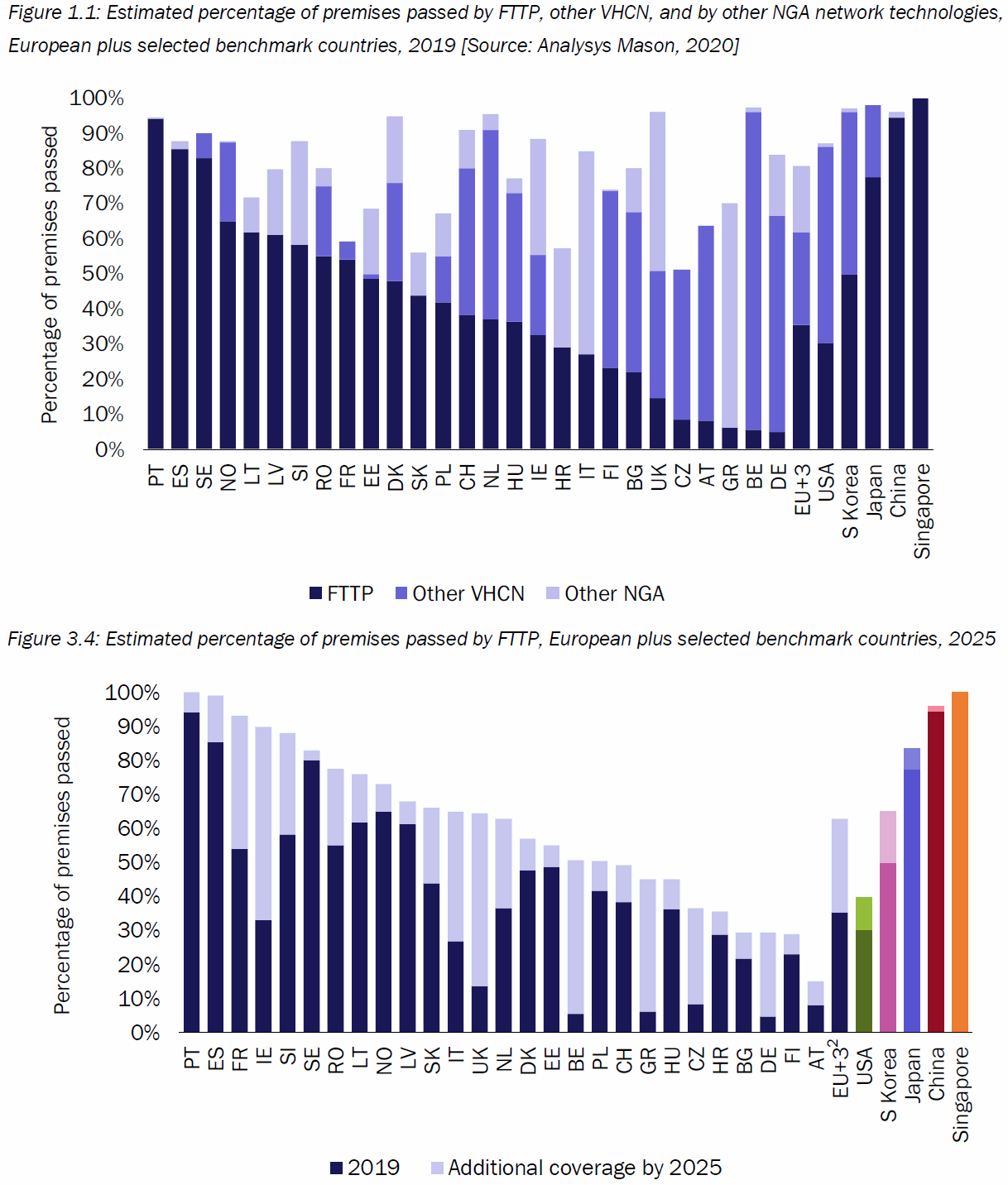

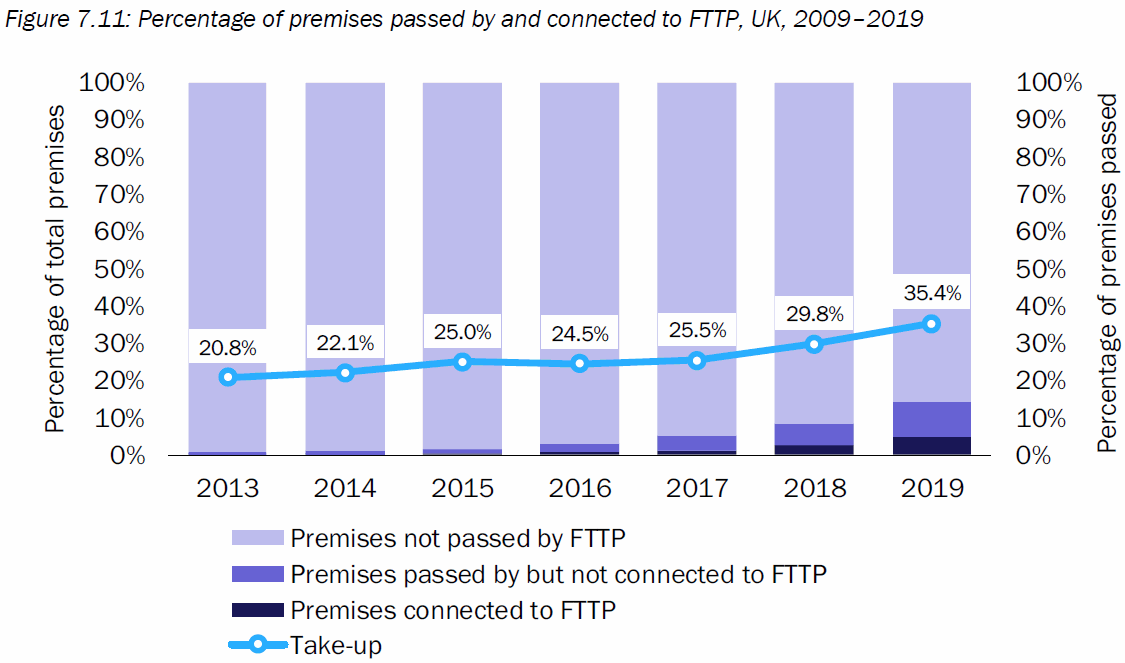

At present the United Kingdom actually does quite well in terms of so-called “superfast” (aka – NGA) coverage at speeds of 30Mbps+ (around 96-97%), while a little over half of premises can order an “ultrafast” service of 100Mbps+ (aka – VHCN) – mostly thanks to FTTP and Virgin Media’s hybrid fibre DOCSIS. But sadly “full fibre” (FTTP) networks can only cover around 14% of premises.

We should point out that Virgin Media’s on-going DOCSIS 3.1 upgrade will enable 1Gbps+ download speeds to half of all homes by the end of 2021, while all full fibre networks are generally considered to be “gigabit-capable” by default. Sadly the UK’s coverage of VHCN and FTTP remains poor when compared with our peers, with Analysys Mason predicting FTTP alone to reach just c.65% of premises by 2025.

The good news is that, over the past few years, we’ve seen a significant ramping-up of commercial FTTP deployments in the UK. “While many of these are still ‘ambitions’ rather than fully funded plans and therefore may not be realised, the total alternative operator coverage ambition amounts to over 20 million premises, two-thirds of the UK. Openreach has an ambition ‘given the right regulatory circumstances’ to reach 20 million by the mid to late 2020s,” said the report.

Advertisement

Much of this progress can be linked back to a combination of various policy / regulatory changes (e.g. making Openreach’s existing cable ducts more accessible to rivals) and investment schemes (e.g. the £400m digital infrastructure fund, LFFN, gigabit vouchers, BDUK etc.), which have helped to drive alternative network (AltNet) ISPs to build and these in turn have put pressure on the big operators to go further.

All of this investment and progress is very welcome, but Analysys Mason warns that its “fragmented nature may pose problems in the future,” such as inefficient overbuild (e.g. most of the commercial UK build is in urban areas where overbuild does little to help overall coverage, but it does aid competition for consumers), significant gaps in coverage, and a legacy of different architecture and suppliers that would be difficult to consolidate if that were required.

Solving such issues won’t be easy and strong competitive interests often have a tendency to turn such efforts into an attempt at herding cats. Nevertheless the new research appears to fancy its chances at the cat herding game and has made several recommendations, which largely focuses upon FTTP as being the best long-term solution.

Advertisement

Summary of General Recommendations

1. Demand is strong and does not need to be defined solely in terms of bandwidth. Bandwidth demand will move on over time, but fibre itself is a one-off. It is equally vital to recognise the long-term (many decades) advantages in terms of operating efficiency, service possibilities and environmental protection. True technology agnosticism should also encourage as far as possible the full panoply of future-looking technologies (NG-PONs, 5G/6G, Wi-Fi 6/7 and their successors), and of course of services in the digital ecosystem

2. A more dirigiste approach is required (i.e. an economic doctrine in which the state plays a strong directive role). Enabling the conditions for flourishing competition-driven innovation and service improvement is where public money is best spent, and it is to this end that policy should be directed.

3. Policy should treat fibre as infrastructure and should encourage a diversity of vendors, a diversity of operating companies and diversity of services that use it. It should encourage options for access at as low a layer as is feasible: this means a preference for physical infrastructure access or dark fibre access. Public money, where required, should preferably be spent enabling low layer access.

4. In countries, or in regions of countries, with little relevant physical infrastructure, public money may be better spent creating ducts for competing fibre infrastructures. Absence of duct access now looks like the largest single obstacle to FTTP roll-out in the most ‘difficult’ European countries.

5. As an alternative to duct build, policy should encourage or mandate the building of networks with end-to-end multi-fibre. This is a critical feature of the successful network in Singapore and of the new Open Fibre network in Italy. Layer 1 unbundling worked on copper networks to the benefit of end users (lower prices, less of the artificial price differentiation based on speed typical of Layer 2 bitstream), and there is every reason to believe it also will on FTTP.

6. Where private investment is flourishing, governments should avoid crowding out private investment. However, a completely laissez-faire approach is unlikely to prove optimal in the long run, and risks a re-run of the market failures of CATV roll-out at the end of the last century. In some markets, retro-fitting a more managed approach to fibre, along the lines of the French model with its regional franchises and its de-risking balance of obligations and rewards, may avert inefficient investment and patchy or disappointing outcomes for end users and failures for investors. Oversight of already commercially negotiated shared networks or mutualised access in non-urban areas could be part of this approach, if this ultimately allows public money to be focused on the most economically challenging areas to be covered.

7. Governments should impose stricter and more forward-looking building regulation. FTTP-readiness even before the ODN is built is an obvious place to start. It would be even more future-looking to impose or encourage the installation of mini-OLTs/passive optical LANs across rooms in new buildings, which would be relatively low cost in the context of total construction costs.

8. Governments should take measures to combat the shortage in skilled workforce required for the mass deployment of fibre. Since roll-out has been uneven in Europe, there will be some pools of skilled labour from countries where most of the roll-out has been done. However, the other logical response to construction capacity shortfall is to encourage as far as possible any means that industrialises the process of roll-out, thereby simultaneously digitalising desk-based planning and file-based paperwork, and deskilling and accelerating the rate of roll-out.

9. Governments should consider tax incentives on fibre network build and on fibre customer connections. A copper scrappage scheme with a guaranteed price for scrap should also be considered.

We should point out that some aspects of the above are already happening in the UK. For example, on no.4 we already see public money being spent to help build new Dark Fibre networks for the public sector (e.g. Local Full Fibre Networks), which can later be expanded to homes and businesses via private investment.

Likewise several new policies are currently being implemented that will help to push fibre into new build homes and existing MDU buildings, which is similar to no.7 above. However other areas, such as combating the shortage of skilled engineers (e.g. no. 8), probably won’t be helped by Brexit and COVID-19 related travel restrictions.

Speaking of Brexit, the report says it is “possible that the UK could push a more pro-investment line after it leaves the EU,” but that will not happen immediately and in any case no solid proposals have been set out yet to show how this would work (e.g. we might see more acceptance of closed rather than open access networks where public money is concerned).

Finally, there’s a brief mention of unbundled fibre (the main suggestion appears to be wavelength unbundling), although we can’t see Ofcom putting anything like that forward for quite a few years. Building FTTP is hugely expensive with a long payback window and the regulator has recognised that forcing an operator, such as Openreach, to unbundle FTTP too early would discourage their investment.

We should add that the UK market for FTTP is currently shaping up to be much more diverse than the old copper one and unbundling also tends to be quite an expensive approach. Otherwise the full report does make for quite an interesting read.

Mark is a professional technology writer, IT consultant and computer engineer from Dorset (England), he also founded ISPreview in 1999 and enjoys analysing the latest telecoms and broadband developments. Find me on X (Twitter), Mastodon, Facebook, BlueSky, Threads.net and Linkedin.

« ISP Truespeed Build Full Fibre Broadband to Saltford in Somerset

Full Fibre UK ISP Hyperoptic Launch Optional Price Promises »

|Err. I don’t think trust those China figures. They must be using a very kind definition of ‘passed’

The UK figure is currently approaching the 14% mark, according to Thinkbroadband’s latest independent estimate. Similarly Ofcom’s January 2020 data put it at 12%, so after several months it should broadly agree with TBB. Suffice to say that Analysys Mason has used a similar figure, so it seems fair.

Not the UK figure Mark. The figures for China. ~90% passed by FTTP. The cities perhaps not the countryside…

Ah sorry, I thought you were making a play on the Huawei association, although China does have a massive amount of FTTH but statistics from that country can be hard to trust.

In fairness I can see my remark could be read the wrong way. ~60% city population makes that 90 number look problematic…just wonder are they using the same def of ‘passed’ or using each countries own def perhaps…

This again shows how far behind this country really is.

Just look at the daily headlines here on ISPReview: Village A has built a new fibre network, Town B has now more fibre, Location C will have fibre soon, etc.

Nobody makes it a news item when a water company connects newly built premises, or when an electric utility is improved. By now it should be a given that a telecom company builds and offers telecom services, just like other utility companies. It is a sad fact that the UK still can’t do that for fibre, for the majority of this country, after more than a wasted decade. The weirdest thing was that in a number of places people had to start local campaigns to get proper telecom services, instead of the telecom just doing their job. How would you feel if you had to do a campaign to get electricity or water to your premises? Is the UK becoming a 3rd world country?

“Nobody makes it a news item when a water company connects newly built premises, or when an electric utility is improved.”

I’m sure if you hunted deeply enough then you could find some like that :). But of course water and electricity are fairly simple linear supplies, while broadband is a highly complex, dynamic and relatively recent commercial service with lots of different delivery methods and levels.

The big difference is that within each area there is only one company responsible for providing electricity or water supplies.

Broadband is provided (or not) by a few large companies, and a whole bunch of one-man-and-a-dog companies, with no overall plan. All are cherry-picking the areas they build, and most have ambitions way outside their abilities.

The result is that some areas have a choice of multiple superfast or ultrafast options, and others have a choice of ADSL or ADSL2+, and no prospect of anything else for years.

What proportion of the country has access to mains gas and the sewer network?

You’ll notice that some of the countries with relatively high fibre penetration don’t have much ‘other NGA’ available, and that’s the payoff. If an operator pursues solely FTTP from the off then people have to wait a long time to get anything beyond ADSL. If 25% of the country had FTTP and the rest were on ADSL I think there would be plenty of complaints.The UK’s approach has been to deliver better broadband to as many people as possible in as short a time as possible. You can’t do that if you go straight for FTTP. It takes too long and costs too much.

“What proportion of the country has access to mains gas and the sewer network?”

Well, in the UK it is quite high, but still some (such as myself and neighbours) have neither gas nor sewers. We do have electricity most of the time, and ADSL2+ is now available (although almost nobody locally uses it as it isn’t fast enough to be useful).

“Likewise several new policies are currently being implemented that will help to push fibre into new build homes and existing MDU buildings, which is similar to no.7 above.”

Hi, I’m just curious what these new policies are for existing MDUs? Unfortunately I’ve recently had issues around this with getting FTTP into my apartment which is part of a small block. Just before Covid19 really kicked off here Openreach had finished some internal work but had something on their own end to complete externally and were aiming originally for the end of March but that was (understandably) pushed back. Would be nice to hear if these policies would open up more options though such as Virgin since we are in a Virgin enabled area but can’t have them installed due to freeholder contracts saying no external cables (even though I own the apartment, which is fair enough it is in the freehold)

https://www.ispreview.co.uk/index.php/2020/01/bill-to-spread-gigabit-broadband-into-big-buildings-gets-support.html