Sponsored Links

EU Slams Copyright Law as UK Admits No Evidence for the Digital Economy Act

Posted: 21st Nov, 2011 By: MarkJ

A key civil servant whom helped author the UK governments 2010 Digital Economy Act (DEA / DEAct), which seeks to tackle "illegal" internet copyright infringement (piracy) by forcing controversial new measures upon broadband ISPs and their customers (e.g. account "suspension"), has admitted that the acts "impact assessment was not based on new research or evidence".

A key civil servant whom helped author the UK governments 2010 Digital Economy Act (DEA / DEAct), which seeks to tackle "illegal" internet copyright infringement (piracy) by forcing controversial new measures upon broadband ISPs and their customers (e.g. account "suspension"), has admitted that the acts "impact assessment was not based on new research or evidence".The comments, which also assert that the only real "evidence" to be associated with the acts construction came from the Rights Holders themselves, is technically nothing new. However both the past (Labour) and present coalition (Conservative / Liberal Democrat) government have preferred not to talk about it.

Civil Servant, Adrian Brazier, told BIS's Parliamentary Select Committee (IPTegrity):

"It is reasonable to acknowledge that the Open Rights Group have something of a point about the evidence used for the Digital Economy Act. It was somewhat opaque. The impact assessment was not based on new research or evidence.

We had no independent source of information. It is probably fair to say that the evidence we had, had been offered by the rights-holders, they were unwilling to lift the bonnet and let us see the engines, if you like the workings and methodology.

We were trying to make the best brick we could with what straw we could find. In those circumstances, I would say however, that we were always clear as to the provenance of the sources we were quoting. We never claimed they were government figures. We were clear that these were figures that were provided by the rights-holders."

"It is reasonable to acknowledge that the Open Rights Group have something of a point about the evidence used for the Digital Economy Act. It was somewhat opaque. The impact assessment was not based on new research or evidence.

We had no independent source of information. It is probably fair to say that the evidence we had, had been offered by the rights-holders, they were unwilling to lift the bonnet and let us see the engines, if you like the workings and methodology.

We were trying to make the best brick we could with what straw we could find. In those circumstances, I would say however, that we were always clear as to the provenance of the sources we were quoting. We never claimed they were government figures. We were clear that these were figures that were provided by the rights-holders."

Credible policies are often those that have been based upon independent evidence and not statistics from obviously partisan sources. For example, the UK government has repeatedly quoted figures from a British Phonographic Industry (BPI) study, which infamously claimed that 7 Million Brits were involved in piracy via P2P (BitTorrent, File Sharing) services.

The BBC later discovered that this data had been gleaned from a 2008 survey of 1,176 net-connected households, 11.6% of which admitted to having used file-sharing software; in other words, only 136 people. As if by magic that 11.6% was then adjusted upwards to 16.3% "to reflect the assumption that fewer people admit to file sharing than actually do it". Hmm.

In addition Rights Holders frequently assume, through related studies, that one "illegal" download is equal to one lost sale. Suffice to say that somebody who downloads 1,000 music tracks is unlikely to have ever brought that many in the first place, although in fairness it could still have some impact upon the creative industry. Proper independent UK studies would have helped to determine the truth.

Now the European Commission's Vice President for the EU's Digital Agenda policy, Neelie Kroes, has weighed into the debate by warning that it has become "increasingly hard to legally enforce copyright rules". Kroes said that the battle was costing millions and had shown no firm signs of "victory". It's perhaps not surprising, especially when Rights Holders often appear to spend more time thinking up new means of punishment instead of solutions to meet legitimate consumer demands (online cinema releases perhaps? Nope, you can't have that).

Neelie Kroes, VP of the EC's Digital Agenda, warned:

"Meanwhile, artists continue to struggle by on a pittance, as the copyright system fails to reward them properly. I was shocked at the number of artists – whether they’re writers, painters, photographers, musicians, whatever – whose earnings are under the paltry figure of 1000 euros a month, less than the minimum wage. That’s pretty devastating, for the artists themselves and for Europe as a whole. Because the creative sector is what we’re good at in Europe – something that could really help us grow in the future, economically and culturally.

It’s not for us to dictate the best business models. But we should have a framework which permits innovation and puts artists at its heart. A system which does not straitjacket art, but which allows new ideas to thrive—for distribution and use as well as production. Because the business models can and should be as creative as the art itself. New areas like cloud computing could transform what it means to buy or distribute an artwork – we need a system flexible enough to respond.

But at the moment, we’re not flexible or responsive enough. Too often the response to innovative ideas – to ideas like Netflix or iTunes – is simply to be paralysed with fear and inaction. Spotify just reached us here in Belgium – a whole three years after it launched elsewhere in the EU! Ideas shouldn’t take so long to spread within a single market."

"Meanwhile, artists continue to struggle by on a pittance, as the copyright system fails to reward them properly. I was shocked at the number of artists – whether they’re writers, painters, photographers, musicians, whatever – whose earnings are under the paltry figure of 1000 euros a month, less than the minimum wage. That’s pretty devastating, for the artists themselves and for Europe as a whole. Because the creative sector is what we’re good at in Europe – something that could really help us grow in the future, economically and culturally.

It’s not for us to dictate the best business models. But we should have a framework which permits innovation and puts artists at its heart. A system which does not straitjacket art, but which allows new ideas to thrive—for distribution and use as well as production. Because the business models can and should be as creative as the art itself. New areas like cloud computing could transform what it means to buy or distribute an artwork – we need a system flexible enough to respond.

But at the moment, we’re not flexible or responsive enough. Too often the response to innovative ideas – to ideas like Netflix or iTunes – is simply to be paralysed with fear and inaction. Spotify just reached us here in Belgium – a whole three years after it launched elsewhere in the EU! Ideas shouldn’t take so long to spread within a single market."

The Digital Economy Act (DEA) itself remains someway off full implementation and has been held up by various legal challenges (here), technical problems (here and here) and political disagreements. Many of the issues appear to stem from a serious misunderstanding of how the internet itself works, the ISPs ability to control online content (or lack thereof) and how consumers actually use online services.

Search ISP News

Search ISP Listings

Search ISP Reviews

Latest UK ISP News

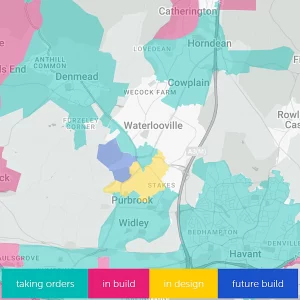

Cheap BIG ISPs for 100Mbps+

150,000+ Customers | View More ISPs

Cheapest ISPs for 100Mbps+

Modest Availability | View More ISPs

Latest UK ISP News

Helpful ISP Guides and Tips

Sponsored Links

The Top 15 Category Tags

- FTTP (6799)

- BT (3881)

- Politics (3075)

- Business (2767)

- Openreach (2663)

- Building Digital UK (2512)

- Mobile Broadband (2475)

- FTTC (2142)

- Statistics (2128)

- 4G (2092)

- Virgin Media (2024)

- Ofcom Regulation (1779)

- 5G (1732)

- Fibre Optic (1604)

- Wireless Internet (1595)

Sponsored

Copyright © 1999 to Present - ISPreview.co.uk - All Rights Reserved - Terms , Privacy and Cookie Policy , Links , Website Rules