Ofcom Publish Final Results from the UK 4G and 5G Mobile Auction

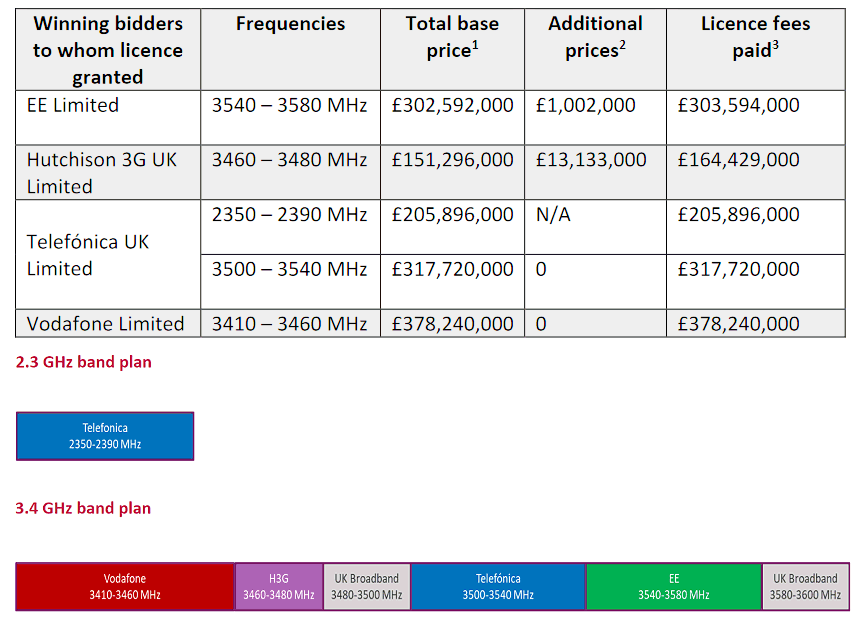

As expected the UK telecoms regulator has today finalised precisely how much extra mobile spectrum has been won in the recent auction of the 4G friendly 2.3GHz and future 5G targeted 3.4GHz radio spectrum bands, which saw EE (BT), O2, Three UK and Vodafone spend a total of £1.37bn.

Overall some 40MHz of frequency in the 2.3GHz band (2350-2390MHz) and 150MHz in the 3.4GHz band (3410-3480MHz and 3500-3580MHz) is being redistributed for use by Mobile Network Operators (much of this was formerly assigned to the Ministry of Defence). Ofcom’s spectrum cap, which was designed to help rebalance the market (previously EE had a fair bit more mobile spectrum than anybody else), meant that EE could not bid on the 2.3GHz band but they did win a slice of 3.4GHz.

The 2.3GHz band is considered “immediately usable” because many existing 4G based Smartphones and other devices are already capable of harnessing it, while the 3.4GHz band is highly prized because it’s intended for use by future multi-Gigabit capable 5G services. Ofcom says the latter will be needed in order to help MNOs to launch “very fast” Mobile Broadband services from 2020.

Advertisement

The principal stage of bidding revealed that the four primary MNOs paid a total of £1,355,744,000 to gain various chunks of spectrum in the auction (here) and today’s final assignment stage (i.e. operators bid to determine where in the frequency bands their new spectrum will be located) figure only adds a little extra to total £1,369,879,000. By comparison Ofcom’s previous 2.6GHz and 800MHz 4G auction raked in £2.367bn (here).

All money raised from the auction will now be paid to HM Treasury. The winning bidders have also been issued with licences to use their relevant spectrum holdings.

In the end O2, which we expected to spend big in order to support their plans for a possible £10bn market listing or sale (value boost), was the only operator to grab the entire 2.3GHz band and they also got a good chunk of 3.4GHz. Sadly Three UK missed yet another opportunity to grab a good chunk of spectrum but their £250m purchase of UK Broadband Ltd. (Relish Wireless) in 2017 has already given them quite a bit to play with (here).

Advertisement

Overall Three UK now claims to have access to a total of about 144MHz (frequency) across several 5G friendly mobile bands (e.g. 3.4-3.6GHz and a bit of 3.9GHz, 28GHz and 40GHz), which actually puts them in quite a strong position for when the main commercial 5G rollout begins in a couple of years’ time (after that it will take a few years to reach near universal UK coverage), but their position in 4G may have weakened.

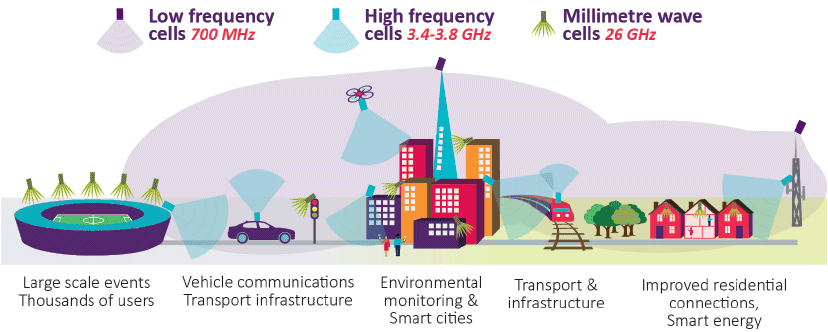

Ofcom also plan to auction off further 5G friendly bands over the next couple of years, including the coverage obligation attached 700MHz band, as well as 3.6GHz and 3.8GHz. We also expect them to auction off some significantly higher frequency mobile spectrum in the 20-30GHz+ bands.

Generally it’s envisaged that 700MHz will prove useful for cheaply delivering wide 5G coverage in rural areas, albeit not to the same service speeds as mobile broadband networks in urban areas that can be combined (Carrier Aggregation) with higher frequencies over shorter ranges.

After that the bands around 3.4-3.8GHz will focus on urban areas (limited range will confine their use to areas of high demand) and of course the higher frequencies at or above 24GHz (millimetre Wave) should support “very large bandwidths, providing ultra-high capacity and very low latency” (i.e. multi-Gigabit fixed wireless links to homes or businesses).

Advertisement

As always the biggest challenge for 5G will be in matching the hype against the laws of physics and economics. 5G will be an excellent multi-Gigabit capable Mobile Broadband upgrade from the existing networks but a lot of what politicians are promoting for it could be achieved today via existing 4G networks. Indeed we are already seeing some 4G networks, under ideal conditions, that are able to deliver end-user speeds of around 1Gbps.

Arguably a far bigger challenge for 5G will be on the capacity side, not least in terms of customer usage allowances (it’s no good having Gigabit speeds if operators can’t deliver significantly bigger data allowances) and the difficult challenge of feeding such hyperfast networks with appropriate levels of capacity. The need for wider coverage of pure fibre optic (FTTP/H/Ethernet) lines goes go hand in hand with 5G.

All of this is easier said than done and no doubt early 5G services will also attract a higher price tag to help compensate for the hefty network upgrade / spectrum costs. In the end 5G will be a big improvement but it’s not that far removed from the earlier 3G to 4G jump and feels more like a logical progression than a truly radical shift. Roll on to the next auction.

Mark is a professional technology writer, IT consultant and computer engineer from Dorset (England), he also founded ISPreview in 1999 and enjoys analysing the latest telecoms and broadband developments. Find me on X (Twitter), Mastodon, Facebook, BlueSky, Threads.net and Linkedin.

« INCA Claim Alternative UK FTTP Networks Reach 1 Million Premises

Comments are closed